|

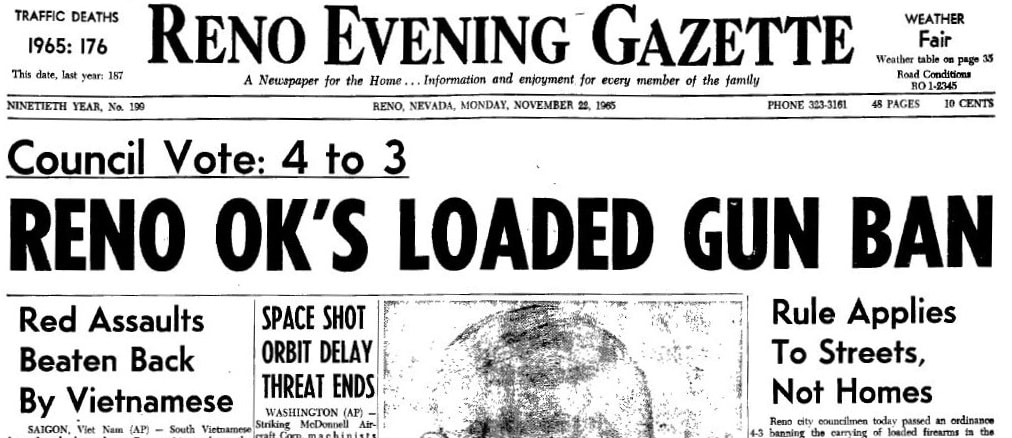

Many Nevadans think Clark County is the capital of gun control in the Silver State, but historically, Washoe County and Reno in particular were the most hostile to the Second Amendment and had the most obtrusive gun regulations in the state. For much of the 20th century, until 1999, loaded open carry was illegal in Reno. Few know just how perilously close Nevada to becoming a gun control state. Traditionally, concealed carry was preferred to open carry, which was seen as a rural or outdoorsman’s practice. Urban open carry was largely unheard of and cause for spectacle, even in frontier towns. Despite open carry being legal, the overwhelming majority of Americans choose to carry concealed, even if breaking the law, or not carry at all, sometimes to their detriment. This right, long affirmed by state courts, was forgotten and the resurgence around the year 2000 took many by surprise. The lack of practiced open carry was a catalyst in the shall-issue wave of concealed weapon permit laws of the 1990s. Like many places in the West, Nevada had state concealed weapon bans off-and-on throughout its early history. Despite this, men continued to carry. Lax attitudes towards violence created an atmosphere where society largely excused the killing of men left the world better off dead. Sick of the violence, concealed weapons were banned as an attempt at a solution. Local ordinances that varied from one place to another banned concealed, or sometimes even all firearms. The laws were ineffective, leading to various state schemes that increased in severity until the 1920s. History is clear; the concealed weapons ban did not stem violence. What changed was that frontier society (where much violence was) began to strongly disapprove of easy killing and fighting over petty matters. It seems that the most effective laws were ones to provide for better resolution of disputes in civil court and criminal justice reform, including laws detailing what exactly self-defense and justifiable homicide was. Until laws were reformed, juries would find men not guilty if they cited even a bare, unsubstantiated fear, providing the dead man wasn’t too well liked. Concealed weapons, versus openly carried weapons, were stigmatized for two reasons. First, concealed carry has always been more popular than open carry. Second, the fear of a man going for a hidden weapon—a furtive movement—was responsible for many preemptive killings. Guilty by association, concealed carry received a reputation as something only degenerates and criminals practiced. If a man felt the need to go armed, he should carry his revolver openly. Few did. In 1903, Nevada passed a law prohibiting concealed weapons in cities, towns, villages and on trains or stages. Permits could be obtained by applying to the county commissioners and demonstrating need. A reporter from the Daily Nevada State Journal made multiple citizens' arrests of the Reno police chief and several officers for carrying concealed weapons as the statute mentioned "any person" and did not exempt law enforcement. The officers reluctantly admitted the reporter was right and the reporter's point was made. In Washoe County, no concealed weapon permits were issued between 1917 and 1944, when two businessmen received temporary permits to carry pistols. The commission planned, in a draft ordinance to deny concealed weapon permits to all but those "who cannot avail themselves of police protection." The county commissioner system was changed to the sheriff in 1959 in a bill proposed by Sen. Floyd Lamb (SB93). The concern was that the commissioners were "not in a position to know the background on all applicants" and that "the sheriff can exercise greater control." In 1993, a “shall issue” concealed carry bill failed for lack of support among law enforcement. Inertia had not quite built up nationally to catapult the law into effect in Nevada on the first try. Once again, preserving local laws were a paramount concern. Barney Dehl, Chief Deputy of Washoe County Sheriff, said “A concealed weapons permit should be limited to persons who did not pose a threat to public safety.” He directly referenced Reno’s ordinances (then in force), complaining that the proposed bill would allow concealed firearm permits to override local ordinances. “He alleged as the bill currently stood, the cities and counties would not have the authority to limit any place in their jurisdiction where weapons could not be carried.” Time has proven these fears were unfounded. Only in 1995, did Nevada get a “shall issue” concealed firearm permitting system, much to the opposition of law enforcement. As passed, the bill created NRS 202.3673, which for a few years banned concealed carry in public buildings of every type, but not public places as in Reno. Two Incidents, Lasting Effects In November of 1965, at the behest of police chief Elmer Briscoe, the Reno city council took up an ordinance to ban the open carry of loaded weapons. Briscoe was a supporter of gun control, including the proposals making the rounds during the 1960s like handgun registration and three-day waiting periods on purchases. Other proposals like banning non-citizens (green card holders) from owning guns had been making the rounds over the years, but few managed to stick. The ordinance had its roots in two incidents. These are the two lone examples of gun scares or open carry issues, at least that were reported, at the time. It seems more likely that the incidents were overblown by the police chief and pushed by powerful interests. One incident was where a mental patient from California stepped off a bus in downtown Reno with two handguns on his hips. Another man walked into a casino restaurant, with a least a revolver on his hip and possibly carrying other weapons, “looking for” a security guard. Accounts vary, including that the man was a hunter carrying a revolver who simply went into the casino. Exaggeration of the details may not be out of the question, as will be seen shortly. The “hunter” was charged under a city ordinance that made it illegal to 'wear, carry, or conceal' a dangerous weapon. At trial, the Washoe District Court Judge found that the city failed "to show the weapon was concealed." The assistant city attorney said that this invalidated the ordinance, as "its intent [as per the judge] is to ban the carrying of a weapon that is concealed." He asked the city council to either repeal or amend the ordinance, proposing that "it apply only to the open carrying of wearing of dangerous weapons" by removing "conceal" from the text. It is strongly implied that the appeals judge deliberately did not apply the ordinance as the weapon was a carried openly. An editorial criticized "It's pretty difficult for a layman to understand that the phrase 'wear, carry or conceal' requires the prosecution to prove concealment...” The original ban from 1905 stated it was illegal to “wear, carry, or have concealed upon his person” a number of weapons. Likely, the judge made his decision on a syntaxial basis, imaging commas to create the grammatical effect of making “wear, carry, or have” apply to only weapons that were concealed. Apparently, the 1905 city council meant to ban concealed weapons and dangerous weapons worn, carried, or had on the person. Since the 1905 ordinance was invalidated, the city council prepared a new ordinance, which would persist as 8.18.010 of the municipal code until 1999. The ordinance banned carrying concealed firearms without a permit (duplicating state law), prohibited carrying wearing loaded firearms in public places or on public streets and also any casino, bar, bank, cabaret, theater, park, school or playground without police permission, and permitted peace officers to inspect firearms on demand to determine if they were loaded. The hysterical Chief Briscoe defended his support of the ban thusly: How is a police officer to determine if a guy carrying a gun in his belt is not intending to hold up some place? If hunters have small caliber pistols, I see no reason why they can't secure these guns the same as they do with rifles. Hunters don't walk into restaurants to have breakfast with loaded rifles in their hands. I don't feel people should be allowed to walk around with guns at their sides just because there is nothing to prohibit them from doing so. I would hate to be standing in a bank lobby when four men walked in carrying guns. Oh, I would think, 'It is okay. They are just going hunting?' This would give a lot of bank officials gray hair. ...we should have some control over the indiscriminate carrying of firearms. There are undesirable people who could take advantage of the fact that we don't have any law against the open carrying of weapons. Every law we have penalizes a few people for the sake of a lot of people.  Reno's 1905 ordinance Reno's 1905 ordinance The appeal was questioned by Councilman Hunter who said that the obvious intent of the ordinance was specifically intended to prohibit both open and concealed carry. Councilman Chism said "Who would want to carry a loaded gun around in public? Anyone who wants to is up to no good. And he is the type we do not want carrying loaded guns around." Another councilman said "it is a fundamental teaching of sports groups not to carry loaded firearms around." The ordinance immediately "came under heavy fire.” One editorial opined "some people even brought the U.S. Constitution into it." Chief Briscoe thought that liberty should suffer for public safety, a view not at all uncommon among late 20th century law enforcement leadership. "Unfortunately, sometimes laws have to be passed to protect the people from themselves. This law would be for the protection of the community. I don't think it would penalize the community." He would have made a communist proud. Chester Piazzo, president of Sportsman Inc. said in opposition "robbers are not the types to carry firearms openly." Another businessman, Charles Beaman, sad "I live in constant fear of robbery. It is not the robbery so much, but being mugged, stomped upon, or pistol whipped." Both Piazzo and Beamen carried pistols to and from work. Either pass a very restrictive law, or let the state law cover and forget it. If it's against the law to carry a gun into a casino, then it ought to be against the law to carry one into a grocery store, a department store—or what have you. And it probably won't be long until the operator of some such business requests his type of enterprise be added to the list. Then another—and another, until the confusion will make the ordinance meaningless. Which happens when you start to compromise to mollify both sides. of firearms. There are undesirable people who could take advantage of the fact that we don't have any law against the open carrying of weapons. Every law we have penalizes a few people for the sake of a lot of people." A councilman suggested prohibiting only loaded pistols, to which Briscoe replied "An unloaded pistol is just as much a threat as a loaded one because you do not know if it is loaded." Briscoe’s suggestion was not heeded. A little known joke is that during the second half of the last century, the Second Amendment only applied to hunting (except with a machine gun), at least in the minds of many, as it continues to persist in the opinions of many anti-gun individuals and politicians. Thankfully for the Washoe sportsman, Briscoe wanted to protect hunters. Chief Briscoe stated that hunters would be recognizable, as "they are appropriately dressed and on the streets at certain hours of the day," but that he would know a man carrying golf clubs and a .45 would not be a hunter. Despite public outcry, the ordinance was passed, but exempted unloaded firearms, mirroring provisions of California’s later Mulford Act. According to Charles Beaman, a laundromat owner, the ordinance was passed "because of pressure from casino operators,” certainly nothing new in Nevada. Opposition by the public was apparently limited. The NRA would not transform into the heavily politically involved organization is today until the 1977 “Cincinnati Revolution.” Today, a similar proposal would be met with a flood of negative publicity. Lawsuits would be legion. However, in the days before the Internet, only legal experts with access to a myriad of old court decisions could prove that across the country, open carry was the constitutionally preferred method of carry. In fact, for most Americans, it was not until the publication of the Ninth Circuit Court’s final decision in Peruta v. Gore that Second Amendment advocates became aware of the open carry cases. Again, one must remember this was a different time in America where urbanites largely forgot about their right to self-defense. In the 1960s, the consensus among some that carrying guns for self-defense didn’t make people safe was nothing new. Even in the 1930s, relying on city police was considered the “right” thing to do. Since police protection is pretty effective in most cities, even for tourists who are guests of the cities, the simpler way might be to make the possession of guns a some what more difficult matter. Few citizens have ever bettered their position by the use of firearms. Las Vegas was a dusty, rural backwater by comparison then, while Reno was a well-known, almost cosmopolitan, city. The peaceful times that Reno residents experienced in their lives were far from the Wild West days where the local sheriff was far away. Only after the turbulent and bloody years from the mid-60’s on would public opinion change to support daily self-defense carry. Attitudes Ten years after banning open carry, Reno police warned its "jittery women" not to carry loaded guns in public without permission of the chief of police. A 1971 senate bill was proposed at the request of a citizen to allow women to carry mace, then considered a concealed weapon. Carson Sheriff Robert Humphrey opposed the bill, proud of his record of denying the right to bear arms. "I don't think a woman is going to be able to get mace out of her purse and use it effectively. It might give a woman a false feeling of security and cause her to be hurt more than if she didn't have it. I've never issued a concealed weapon permit and never will and I feel the same way about mace. If a person has it, they're going to be looking for an excuse to use it." Elsewhere Stupid gun laws are not limited to just the urban counties. In 1984, Mineral County Sheriff John Madraso Jr. proposed to expand the town of Hawthorne's 1946 ban on concealed weapons to the entire county. The public was incensed and flooded the county commissioners' meeting. Allegedly, it would require registration of anything definable as a weapon, including any sharp object, and ban openly carried weapons. Madraso claimed that the changes were needed because of 20 cases of persons calling about openly carried weapons, some of which were taken into schools. At the time, it was not illegal under state to carry a firearm into a school. Madraso blamed DA Larry Bettis for the uproar, who blamed the sheriff in return. The ordinance was not passed. Hawthorne’s 1946 ordinance is still on the books of the Mineral County Code. Preemption In 1987, light appeared at the end of the tunnel. Florida was leading the nation with its efforts to create a shall-issue concealed weapon permit system. Self-defense carry and handgun ownership was beginning to re-emerge from its long stigma dating from the days of the Old West. All fronts of the Second Amendment were not in sunshine, however. In 1981, the city of Morton Grove, Illinois, decided to ban ownership of handguns and the Supreme Court did not hear the appeal. Concerned for such abuses spreading, over thirty states passed laws to prevent local governments from making their own abusive gun control laws. Assemblyman Dini touted that the preemption bill would prevent panic legislation (as happened in Reno in 1965). State preemption of firearm regulation was first proposed in 1987 as AB 288 by Assemblyman Thompson of Clark County. He vehemently denied dogged accusations that preemption was at the behest of the NRA, but drafted at a constituent’s request. "The point is, [preemption] is not part of some nefarious plot, or secret scheme,” he later said in response to those baseless allegations the “gun lobby” was trying to weaken law enforcement. Opposition, largely by LVMPD, was intense and caused the bill to die in the 1987 legislative session. In 1989, Thompson proposed AB 147, which ultimately became law. In its original form, the various changes to preemption, including enhanced preemption of 2015, would have been unnecessary. Once again, the powerful forces of LVMPD doomed the provisions that would have put all localities on an even playing field. Reno police were in opposition as well as they would lose their open carry ban ordinance. Clark County and Metro officials objected because their three-day waiting period and handgun registration (“blue cards”) ordinances would be invalidated. Undersheriff Cooper said that "Las Vegas was becoming a major city with major city problems, therefore, Las Vegas could not be compared to the remainder of the state." Metro fear-mongered that public safety would suffer and detectives would stumble blindly through criminal investigations. Sheriff Moran said: "[...] I think Las Vegas is a very unique city and requires gun regulations that would be impractical in rural areas. [...] Las Vegas is unlike any other city in the world. [...] but there comes a time when even I have to interpret the Constitution as I see fit [emphasis added]." Moran’s statement shows the shocking arrogance of law enforcement leaders of the time and why Metro in particular was so dead-set against preemption laws and for strictly restricting citizens' Second Amendment rights (until Sheriff Lombardo saw the writing on the wall). Unable to overcome Metro’s opposition, Assemblyman Garner suggested grandfathering all local laws already in existence. The intent of the grandfather clause was specifically to preserve Clark County ordinances, which Metro practically begged to keep. As a side effect, Reno’s ordinances also remained in effect, which was not at all the aim of the bill. AB 147 passed and state preemption of firearms laws became Nevada law. Only the legislature could regulate guns, except for unsafe discharge of firearms. Yet the bill failed in its original purpose; as a result of Garner’s amendment to grandfather in existing laws, only future regulations could be prevented. Clark County and Reno’s law remained on the books and enforceable. For Nevadans, nothing would change except to alleviate fears of ordinances getting worse. Preemption was dreadfully weak and had no teeth. In 1999, John Riggs, a member of the now-defunct Nevada State Rifle and Pistol Association, successfully petitioned the Reno city council to repeal their ban. Ordinance 5035 made open carry legal in Reno once again. Details behind this action seem to be lost to history. It is unknown if the ban had been enforced in recent times. One by one, prior to 2015, effectively all the local legal obstacles to open and concealed carry were repealed, except in Clark County. Even in the counties that didn’t repeal their ordinances, active enforcement stopped long before 2015. Notably, in regards to Clark County’s park gun ban ordinance, Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto wrote an opinion justifying the enforceability of pre-1989 local ordinances and regulations. This directly led to the call for enhanced preemption. Under Cortez Masto’s logic, as long as the ordinance or regulation had not been altered since 1989, it would continue in force. SB 92 of 2007 should have invalidated all local ordinances, as it did not contain the 1989 bills grandfather clause, but corruption prevailed and local laws stayed. Without the success of enhanced preemption being signed into law in 2015, Reno’s open carry ban would have stood for nearly fifty years, long into the era when openly carried guns were once again nothing to get excited about. Conclusion Today, anachronisms remain on the books in northern Nevada. While most local regulations go unenforced, they have no place under the law. Washoe and Mineral Counties are in violation of the law for failing to repeal its conflicting ordinances on the carry of weapons. Some of the local laws, such as sale or possession of weapons by minors, are now covered by state law. Whether discharge ordinances area “unsafe” discharge ordinances is up for debate. Those laws, while not bothering anyone, need to be removed as well. However, our focus need to be first aimed at expunging the offensive legacy of gun control in northern Nevada, particularly the remaining laws in Washoe and Mineral Counties. One by one, the small issues can be corrected, but first and foremost, the ugly scars remaining among the ordinances of those counties must be erased. Related article: Washoe County Still Violates State Preemption Sources

Last week, the Nevada Firearms Coalition set off a firestorm on Facebook when it posted a question, “How many know that Campus Carry is already legal in Nevada?” Stimulating discussion was the goal, and it certainly did. Of course, only with written permission of campus authorities, may a concealed firearm permittee carry on campus. A person seeking to carry concealed on campus sends a written request to the campus president for consideration. What if you asked for permission and were told not even to bother? That is the way that Nevada treats armed citizens who apply for permission. Requests are regularly denied, including one for an off-duty corrections officer. Several persons have reported that even asking “How do I apply?” is me with “Don’t bother, they don’t approve anybody.” The right to effective, preemptive self-defense on college and university campuses has been denied to Nevadans. State law provides for the Nevada System of Higher Education (Board of Trustees) to create a policy for all public colleges and universities to guide the individual campus presidents in granting permission. The policy cites part of the landmark Supreme Court case, DC v. Heller, to justify its ban, calling colleges and universities, “sensitive” spaces. “The statutory prohibition of weapons, including firearms on campus, is longstanding,” the policy reads. The “longstanding” prohibition of NRS 202.265 dates from 1989’s AB 346. As drafted, the law originally applied only to high schools as there was a problem with students, usually involved in gangs or drugs, who brought weapons to school. Colleges and universities were added after the bill became public. Before that, only student codes of conduct prohibited weapons without permission, originating after concerns about student riots. Not What You Think Today’s monolithic denial policy was not the intention of the legislators who crafted the first ban on guns in schools. In 1989, open carry was uncommon, concealed carry permits were “may issue” with need, and many Americans scoffed at the idea of carrying a gun for protection. The campus carry ban is a product of its time and an anachronism when most Americans accept concealed carry as a right. School shootings were tragic crimes and a far-fetched possibility, not “an epidemic” and reasonable fear as they are now. 1989’s AB 346 was sponsored by Assemblyman Gaston, apparently at the behest of Clark County District Attorney Ken Hicks and the Clark County School District. Schools there were seeing increasing problems with crime, escalating to possession of firearms on campus. Expulsion was not enough of a penalty to deter students from bringing guns on campus. “Students feel that guns enhance their image...The kids are laughing up their sleeves at the system,” DA Hicks said. The original draft only referred to "a private or public school" and exempted those with "written permission from the principal of the school." Law enforcement suggested a ‘gun free school-zone’ perimeter around the school, but this was apparently never acted upon due to constitutional concerns. Clark County School District (CCSD) officials requested a violation be a felony to discourage non-students, explaining that at the time, an openly carried weapon (by an adult) would be perfectly legal and the threat of expulsion was not a deterrent. From the context of the hearing, it appears that self-defense carry in today's context was not the issue, but criminals or gang members close in age to the students may have been the concern. "Right now a kid can come on the school campus and have his Uzi on the seat of his car and there is nothing we can do about it," said Mr. Koot of the DA's office. Lost to history is whether or not they indeed wanted to ban innocent open carry or saw open carry as a loophole for a miscreant to exploit. No concern for legal weapons in vehicles, such as a hunter with a rifle in his back window, was shown, legislators suggesting instead that the hunter park off campus and walk his child in. It was felt by a CCSD official that law enforcement would be allowed discretion to ignore such technical violations if they meant no harm. Assemblyman Carpenter seemed to be the lone voice of caution to avoid penalties for law-abiding citizens. After colleges and universities were added to the ban, Senator Wagner objected that a university student with a legal firearm or other weapon in their parked vehicle would be impacted by the law. Assemblyman Gaston reply essentially indicated he did not care that the university student would be negatively impacted. However: "Mr. Gaston remarked the University System was not part of this [the bill] initially as the original intent was directed at high schools, but [the University System] requested to be included." The University System is now known as the Nevada System of Higher Education (NSHE). In response, Henry Etchemendy, representing the Nevada Association of School Boards, stated that student rights were protected because there was "sufficient discretionary authority...by the ability to obtain written permission from a Principal to deviate from general practice." Assemblyman Gaston told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the bill would exempt "anyone who legitimately has a reasonto bring a dangerous weapon [on school grounds] after having received permission [emphasis added]." Discretion So, not only do we see that colleges and universities were secondary to the original purpose of the bill, but discretion, both for police and the educational authorities, was to be exercised. Sadly, they seldom are. Time has shown that discretion without guidance has proved to be effectively a denial of the right to self-defense. For all intents and purposes, only the most extreme or exceptional circumstances (such as an off-duty police officer speaking on campus) justify granting permission for concealed carry. In 2011, only one student at UNR had permission to carry and none at UNLV. Campus carry advocate Amanda Collins had to carry only under the condition of absolute secrecy and only after she was victimized. During the hearings for SB 231 in 2011, she told the Senate Judiciary Committee: I question why it takes somebody being assaulted before being allowed to defend oneself. Also, what makes me special? Why do only I get to defend myself? Am I granted permission because I was assaulted at gunpoint in a gun-free zone? In 2011, UNR had received about a dozen requests and approved one. During the 2015 campus carry legislation hearings, further details came out. Catherine Cortez Masto, former Nevada Attorney General and then Executive Vice Chancellor of NSHE said: With respect to the CCWs on our college campuses, the statistics that I have available show that there were nine requests at UNR last year. Four of them were nongun related because they were for weapons in general. Five of them were for guns. At UNLV, there were three requests last year. At Truckee Meadows Community College, there were six requests. Western Nevada College had one request. I am sure you would like to know how many were denied or approved. Of the nine at UNR, five were denied, and four were approved. Assemblywoman Michelle Fiore addressed the details of the actual approvals: There were 13 concealed weapons permit applications. One was approved, and one was approved for a one-day pass. Therefore, we have one concealed weapons permit to carry on campus which was approved throughout the whole state of Nevada. In her testimony, Mrs. Cortez Masto said there were four approved. As for the other three, I want you to understand that it was not a concealed weapon that was approved. If I was doing a presentation on firearms on one of the NSHE campuses and I wanted to bring in my acrylic AK-47 lamp, which is plastic and not a firearm, I would have to get permission to go on campus with it. Just like this necklace of a firearm that I always wear, they would find it offensive because it is a firearm. These are things that we would have to get permission for. Therefore, the three other permissions granted were for things like that. In 2008, President Lucey of Western Nevada College reported she only gave permission to the Loomis driver who serviced the ATM. NSHE’s Policy Terms Presidents have discretionary authority, subject to the conditions set by the Board of Trustees. The duty of the president is to: An NSHE institution President who receives a written request from an individual to carry a concealed weapon on the campus must consider, investigate, and evaluate each request on a case by case basis, giving individual consideration to each specific request, and must make a determination on each request according to a need standard. Permits are may issue and require a specific “need” under the most stringent interpretation of the word. Determining factors are:

Amanda Collins would not have qualified for a permit prior to her being attacked as the danger of rape was a risk general to any woman, rather than a certain risk to Amanda. Indeed, a cynical and unsympathetic president could even deny a future victim permission to carry if the suspect was apprehended, justifying it as the “specific risk of attack” abated with the attacker’s incarceration. Thankfully, no one here is that cold-hearted. NSHE’s Policy Justification One would think that a policy would outline the specific safety concerns and risks of armed young students that opponents to campus carry always bring up. Instead, NSHE prefaces its regulations not with safety concerns, but with concern for sensibilities. NSHE is committed to providing an orderly academic environment for learning that promotes the acquisition of knowledge and advances the free exchange of ideas. The preservation of this educational environment is an important objective for the NSHE and its institutions...The prohibition contributes to the welcoming and open nature of the NSHE institutions and promotes an atmosphere conducive to learning. Feelings and perceptions trump safety. The only “need” to ban firearms is to avoid offending anti-gun students, faculty, and staff. Time and time again, the criminality and risk from concealed carriers, even college-age students, have been debunked. At this time, there is no justification whatsoever for banning concealed carry on campus and no legitimate defense for maintaining a ban. The facts have spoken; only those who stand recalcitrant to reason choose to deny well established facts and positive experiences from other states. Ultimately, much of the opposition is afraid of firearms. Some don’t understand firearms, and having no experience with them, root their opposition in a fear of what is unknown to them. Others lack the ability to imagine all but the worst cases, letting their emotion of what could go wrong obliterate the evidence that campus carry is no more dangerous than off-campus. And then there are political reasons which bear no need for commentary. Conclusion The sea change in attitudes towards weapons in the hands of individuals changed in less than ten years after Nevada’s school gun ban was imposed. Shall-issue concealed carry passed in 1995. Despite the increasing frequency of high-profile mass shootings, the general trend in the United States has been to remove obstacles to armed citizens. Surely Nevada legislators were moved by the 1999 Columbine killings to enact further legislation. On the contrary. "We've hardly discussed it. You can pass any many bills as you like, but the bad people will still find a way to get a gun," said Senator Dean Rhoads of Tuscarora. Democratic Assemblyman Bernie Anderson said "Our experience is that people who have firearms are responsible users." Non-gun ban related bills were the 70th Legislature's preferred way to address the problems with violence in schools. "Here, most folks believe the concealed-weapons issue has no relevance. But we want to deal with [violence] in other ways,” said a Democrat from Henderson. The historical record is clear; legal guns on college and university campuses have never been a problem. Legislators did not originally seek to deny concealed carriers the ability to carry on campus, but rather allowed it to happen as carrying a handgun legally was uncommon. Authorities were to use their discretion to the benefit of gun owners and not to deny practically every request. Armed citizens and members of the educational community must be involved in the elections and actions of the Board of Regents. Regents who are friendly to gun owners can help create quality policies without resorting to the difficulties of the legislative process. Continue reaching out to students, teachers, and professors about the Second Amendment and the gun culture. 2017 is not 1989. Handguns and self-defense carry are popular in America and once again they are recognized by the majority as not only a right, but sometimes as a necessity. The old conventions about who carries are gun and the risk of accident vs. probability of a defensive gun use have changed. Old policies created under a paradigm that no longer exists and enforced today for political reasons need to be eradicated or altered to reflect today’s reality. Sources:

NSHE Handbook, Title 4, Section 31 Possession of Weapons on NSHE Property NRS 202.265 and NRS 396.110 AB 346 (1989) Legislative History SB 231 (2011) Minutes of the Meeting of the Committee on Judiciary. March 5, 2015. Minutes of the NSHE Board of Regents. Feb. 7, 2008 Gillis, Kyle. "NLV peace officer challenges campus weapons policy." Nevada Journal. May 29, 2012. Frank, George. “code of conduct asked for campus.” Reno Evening Gazette. May 27, 1970. p. 1 AP. "Panel considers bill to ban guns from campuses." Reno Gazette-Journal. March, 1989. p. 4A O'Driscoll, Bill. "Nevada lawmakers shy away from gun laws." Reno Gazette-Journal. June 5, 1999. p. 3 |

Archives

June 2024

CategoriesBlog roll

Clayton E. Cramer Gun Watch Gun Free Zone The War on Guns Commander Zero The View From Out West |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed